Saturday, 16 May 2009

Victoria Beckham Discusses Stripping Off With David Beckham

Friday, 15 May 2009

Beyonce Takes A Beach Break

Week in Review - May 9 - 15, 2009

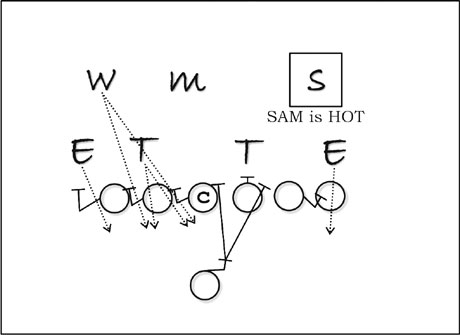

Triple Shoot - Coach Manny Matsakis guest appeared this week to put up a series of posts on his "Triple Shoot" offense. (Sample flavor diagram and video below.)

Check out all four parts in the series:

- Triple Shoot Part 1: History and Overview

- Part 2: Run game and play-action passes

- Part 3: Passing game and exotics (screens)

- Part 4: Conclusion and timeline

Goliaths, Gladwell, and Davids: I was also somewhat fixated on the new Malcolm Gladwell article. If you can only read one thing, read David strategies and Goliath strategies, though this post highlights a good point as well.

Assortments: Also check out some of the assorted links and notes posts here and here. Lots of good links to other sites in those, and also discussions of Rich Rodriguez and Michigan's quarterback situation, Gus Malzahn, the BCS, and of course, some Mike Leach odds and ends.

That's all for now. I'm out of pocket for the weekend, so feel free to leave any comments discussing any of this or anything else -- including ideas for future posts.

Triple Shoot Part 4 - Conclusion

Part 4 - Conclusion: The Triple Shoot Offense from Yesterday to Today

The Triple Shoot Offense started out as a pass-happy offense at Hofstra University (NY) in an attempt to compete versus scholarship schools during our Division III to I-AA transition. We were able to put up some gaudy numbers (42 ppg and 405 ypg passing) and a rather impressive winning percentage. At Emporia State University (KS) we realized that putting up the big numbers was not that big of a deal, what was more important was winning games. In order to do so, we researched and developed an explosive running game (Belly Series) to compliment the pass attack. The results speak for themselves, as we led the competitive MIAA in Rushing, Passing and scoring during the same season and were able to get our Superback to rush for nearly 2,000 yards or more three years in a row (Brian Shay broke Johnny Bailey’s all-time collegiate rushing record in this offense). Not only were our players able to achieve this in a team-oriented setting but our two inside receivers (Pobolish & Vito combined with Shay to garner over 15,000 yards during their careers together, the NCAA doesn’t keep records like that but we have yet to see career production like that in college football).

The Triple Shoot Offense started out as a pass-happy offense at Hofstra University (NY) in an attempt to compete versus scholarship schools during our Division III to I-AA transition. We were able to put up some gaudy numbers (42 ppg and 405 ypg passing) and a rather impressive winning percentage. At Emporia State University (KS) we realized that putting up the big numbers was not that big of a deal, what was more important was winning games. In order to do so, we researched and developed an explosive running game (Belly Series) to compliment the pass attack. The results speak for themselves, as we led the competitive MIAA in Rushing, Passing and scoring during the same season and were able to get our Superback to rush for nearly 2,000 yards or more three years in a row (Brian Shay broke Johnny Bailey’s all-time collegiate rushing record in this offense). Not only were our players able to achieve this in a team-oriented setting but our two inside receivers (Pobolish & Vito combined with Shay to garner over 15,000 yards during their careers together, the NCAA doesn’t keep records like that but we have yet to see career production like that in college football).After making a go of it at the small college ranks, we tested the concept at the Division I level at the University of Wyoming. In a single season, we were able to go from last to first in total offense in the Mountain West Conference versus conference opponents. As my good friend Tony Demeo (University of Charleston, WV Head Coach) said, “You put the Ferrari in the garage after that year.” I got out of running this offense for 3 years as I spent some quality time with Mike Leach (Texas Tech University).

After the stint with the Red Raiders, I took the head coaching position at Texas State University to once again coach this system. In a single season, we were able to go from one of the worst offenses in the Southland Conference to a single season finish of #1 in total offense and were ranked #7 in the nation with this balanced attack. I was relieved of my duties after that season for not taking full responsibility of all aspects of my program and at that point chose to leave the coaching profession.

For the next four years I went into private business to develop regional football magazines. During this time, I also spent time reflecting on my career and the Triple Shoot Offense while consulting with coaches from high school to the professional ranks. On one visit to see my friend Hal Mumme, he made a statement that I should at least start to clinic the offense again and see if it would inspire me to coach again, I did and it worked. I am excited to coach the offense again (Capital University in Columbus, Ohio) and look forward to taking the next step with the Triple Shoot. The offense has since been simplified, codified and developed to a point whereby I really feel that the system can be replicated by underdog teams anywhere in the country.

At this point, I have put together an online coaching clinic to help coaches throughout the country in implementing this system. All the video is in there, the teaching progressions, cut-ups, drills and even archived game clips. If you have any interest in this system, check out the promotional website http://tripleshootfootball.com/ or the actual online seminar website http://tripleshootonline.com/to get started. There is even a blog that chronicles issues relating to the offense http://tripleshoot.blogspot.com/.

I have enjoyed taking the time to share with you and clarify some areas of the Triple Shoot Offense. Good luck this season and if you want to reach me, please feel free to contact me at tripleshoot@gmail.com.

Respectfully,

Manny Matsakis

Thursday, 14 May 2009

Trudi Canavan - The Black Magician Trilogy

...excerpt from the first book...

"We should expect this young woman to be more powerful than our average novice, possibly even more powerful than the average magician."

This year, like every other, the magicians of Imardin gather to purge the city of undesirables. Cloaked in the protection of their sorcery, they move with no fear of the vagrants and miscreants who despise them and their work until one enraged girl, barely more than a child, hurls a stone at the hated invaders . . . and effortlessly penetrates their magical shield."

Well, i feel like i have to commend further about this books...but later guys...so much to say here...

till then peeps...

Oscar De La Hoya is hanging up the gloves

David strategies and Goliath strategies

Malcolm Gladwell's new New Yorker piece is called "How David Beats Goliath," and professes to describe what strategies underdogs -- or "Davids" -- can use to defeat Goliaths. His basic premise is that Davids all too often fall into the trap of playing Goliath's game, which is rarely going to lead them to victory: there's a reason that Goliaths are Goliaths and Davids are Davids. Instead, they should do something unique (the article's subtitle is "When underdogs break the rules") and risky:

Malcolm Gladwell's new New Yorker piece is called "How David Beats Goliath," and professes to describe what strategies underdogs -- or "Davids" -- can use to defeat Goliaths. His basic premise is that Davids all too often fall into the trap of playing Goliath's game, which is rarely going to lead them to victory: there's a reason that Goliaths are Goliaths and Davids are Davids. Instead, they should do something unique (the article's subtitle is "When underdogs break the rules") and risky:The political scientist Ivan Arreguín-Toft recently looked at every war fought in the past two hundred years between strong and weak combatants. The Goliaths, he found, won in 71.5 per cent of the cases. That is a remarkable fact. Arreguín-Toft was analyzing conflicts in which one side was at least ten times as powerful — in terms of armed might and population — as its opponent, and even in those lopsided contests the underdog won almost a third of the time. . . .

What happened, Arreguín-Toft wondered, when the underdogs likewise acknowledged their weakness and chose an unconventional strategy? He went back and re-analyzed his data. In those cases, David’s winning percentage went from 28.5 to 63.6. When underdogs choose not to play by Goliath’s rules, they win, Arreguín-Toft concluded, “even when everything we think we know about power says they shouldn’t.”

So far so good. This is consistent with what I wrote in my post, "Conservative and Risky Strategies (and Kurtosis)." The problem with Gladwell's argument, however, is that although he recognizes that Davids ought not to employ Goliath strategies because it is a game they can't win -- "Arreguín-Toft found the same puzzling pattern. When an underdog fought like David, he usually won. But most of the time underdogs didn’t fight like David. . . ." -- he nevertheless assumes that Goliaths should all be using these David strategies as well, and can't understand why they don't.

This is incorrect. Just as Goliath strategies are often sub-optimal for Davids, David strategies are often sub-optimal for Goliaths. The reason Gladwell seems to miss it is because he doesn't have a broad theory for what makes a strategy appropriate for an underdog. His primary example is of the decision of a basketball team composed of twelve-year girls to use the full-court press in basketball the entire game. He also cites Rick Pitino as an example of a coach who has successfully used a David strategy at various stops, and as further counterfactual to the unsuccessful coaches who forgo using the press. This example has been much discussed and even derided as a descriptive matter in basketball, though Gladwell responds to the basketball points here.

More importantly though, Gladwell is actually right in a sense: the press (in basketball at least), is a pretty decent example of an underdog strategy. He fails to recognize that what makes it as a good underdog strategy is also what likely makes it inappropriate for Goliaths -- it is a high risk, high reward, high variance strategy. One reason it works for underdogs may have little to do with how good it is on absolute terms; the fact that there is increased variance by itself has value for underdogs because it might give the underdog a chance of actually winning. On the flipside, however, while a full-time press strategy might increase a Goliath's chance of blowing out an underdog, it also might result in them losing a game they shouldn't. I described all this previously, but the WSJ Daily Fix (Carl Bialik) does a nice job summarizing it:

To understand why, imagine that the Goliaths — the nickname of Philistine State’s basketball team — typically beat opponents by 10 points. They’re playing an average opponent in their next game. Strategy A, a low-variance strategy will, two out of three times, yield a Goliaths victory between 5 and 15 points (with the rest of hypothetical games played with that strategy falling outside that range, including a very small number of losses). But a high-variance strategy has a much wider range of outcomes, with two thirds of games ending somewhere between a five-point Goliaths loss and a 25-point rout. The second strategy, then, will lead to more games where the Goliaths lose. And that’s particularly costly in single-game-elimination competitions such as the NCAA tournament.

For true Davids, the full-court press might help, particularly if it’s not always expected so opposing Goliaths can’t know whether to prepare for it.

I used this image to visually represent the higher-variance, flattened bell curve of expected results from an underdog strategy. (I also assumed that the higher risk strategy increased the overall expected points too, though, as stated earlier, we need not make that assumption.)

I previously explained this trade-off for underdogs and favorites. For Davids:

It's a well-worn belief that underdogs -- i.e. the kind of severely outmatched opponent that cannot win without some good luck -- must employ some risky strategies to succeed. This has long been believed but now we have a reason, though it also teaches us that there is a price to this bargain. The underdog absolutely must take the riskier strategy, whether by throwing more and more aggressively, by onside kicking, or doing flea-flickers and trick plays. They have to get lucky. In the process, however, they also increase the chance that they will get blown out, possibly quite badly. But isn't that worth the price of a shot at winning? Florida might pick off the pass and run it back for a touchdown; they might sack the quarterback and make him fumble; they might blow up the double-reverse pass. If so, then things look grim. But what if they didn't? And if the team didn't do those things, how can it beat them by being conservative? By waiting for Florida to make mistakes?

And Goliaths:

Think about when Florida plays the Citadel. The Gators have a massive talent advantage compared with the Bulldogs. As a result, what is the only way they can lose? You guessed it: by blowing it. They can really only lose if they go out and throw lots of interceptions, gamble on defense and give up unnecessary big plays, or just stink it up.

A fan or some uninitiated coach might see this as a lack of effort, but another view might be that Florida used an unnecessarily risky gameplan that cost them a victory. And since we know that they would win almost every time, what did they gain by being more aggressive? Even if they gained in expected points, this is something like the difference between a forty-point and sixty-point victory, which ought to be irrelevant.

So Gladwell accurately identifies the fact that Davids should use underdog strategies -- and thus avoid playing the favorite's game as so many do -- he fails to perceive that the corollary is also true: Goliaths shouldn't necessarily use David strategies, either.

Application to football

Basketball aficionados are all over Gladwell, trying to poke holes in his understanding of the press or basketball or whatever. With Gladwell, that's kind of beside the point. The basic premise is true: underdogs win when they make the game theirs, not the favorite's.

The question then is how to determine what are good underdog strategies. Year2 at TeamSpeedKills concludes:

The question then is how to determine what are good underdog strategies. Year2 at TeamSpeedKills concludes:

"The challenges they both [full-court press and Malzahn's offense] present opponents are all the more challenging for their uniqueness."

He should have stopped there, because that's also where Gladwell's argument ends. It's solely about being different.

I disagree. I think being different is merely a dominant strategy: all else being equal, it is better for Goliaths and Davids alike to be be different. Year2 and Gladwell are correct that there are some dominant strategies that Goliaths merely overlook (and I think Gladwell may have assumed incorrectly that pressing the entire game was one of them rather than what it is, a good but high variance strategy).

Jerry of Joe Cribbs Car Wash tries to draw a direct parallel between the press Gladwell discusses and Gus Malzahn's up-tempo no-huddle offense. First, I'm not convinced that going no-huddle is a dominant strategy, better for all teams. A team definitely gains the advantage of endurance, and there is a psychological advantage and all that, but, overall it seems fairly value neutral: it's just the repetition of the same trials over and over again.

Except that it isn't, but in the exact opposite way you'd think. Going extreme hurry-up to get as many plays as possible -- other than endurance, I suppose -- is a Goliath strategy: it decreases variance by increasing the number of trials. The chance of getting only heads and no tails in five coin flips is much higher than it is in a hundred -- i.e. the impact of the law of large numbers or regression to the mean. If Oklahoma has significantly more talent, better schemes, and everything else than the underdog, then the more plays it run the more likely it is to exhibit its raw dominance over the underdog; the underdog is less likely to "steal" a few good plays and get the heck out of dodge. The principle is the same as the difference between an underdog winning a game in a single-elimination tournament and trying to win a seven-game series: the seven-game series is far less likely to produce upsets.

So mere up-tempo, no-huddle is not an underdog strategy (and may in fact be a better strategy for Goliaths).

But what strategies would be good underdog, high-variance strategies? Here are some possibilities.

- Passing. It's very clear that passing is a higher-variance (and higher reward) strategy than running. The nature of passing can vary (if you only throw bubble screens that does not entirely count) but passing repeatedly is an underdog strategy. Now, good passing teams can reduce risk, throw safer passes, and the like. All good. And there is an open question with what mix of passes: Deep ones? Short ones? What blend is correct? That can be sorted out later. The bottom line though is that passing is a high variance strategy that can give an underdog a better chance of winning -- and a better chance of messing up and getting creamed.

- Reducing the length of the game and the total number of plays. As explained above, the higher variance and thus David-favoring strategy is to reduce the number of "trials" -- i.e. plays. This is where a passing strategy and a strategy that involves "shortening the game and keeping it close" might run counter to each other. Incomplete passes typically stop the clock (I can't keep the college clock rules in my brain anymore), as do plays where the ballcarrier goes out of bounds, which is more common on passes (same with the clock rules). If an underdog were to get an early lead, they obviously would love it if the game effectively ended right there. Yes, there is much to say about the problems inherent in not playing to lose and all that, but those are means questions, not ends. And all can agree that an underdog would love to get an early lead in a game against a favorite and have the clock run out as fast as possible.

- High variance defense. This is a difficult question. On the one hand, the defense could go for a blitzing, press type defense that might grab turnovers and get opportune stops, on the theory that you only need a few of these to get an underdog advantage. On the other hand, to an underdog each touchdown given up could be backbreaking, and in any event shortening the game by forcing the offense to march the ball up the field methodically, using up the clock, might be better. Yes people like to talk about "if we have the ball, they can't score" but that mistakes time of possession with possessions. If the underdog can force the favorite to use up a lot of clock and, at minimum, not score a touchdown, and then the underdog can somehow pull of a touchdown itself, then huge advantage to the underdog. On the other hand, pressing defenses that give up big plays periodically might play right into the Goliath's hands because it can score without taking much time off the clock. There is more to this but that is enough for some preliminary thoughts. Likely some mixed strategy is best.

- Other high variance strategies. Although much of the focus is on offensive and defensive strategies, the best bet for the David strategies is likely in the realm of truly high-variance strategies like trick plays or onside kicks. Onside kicking is particularly promising, because it is something an underdog can get better at, would be unique, and can be disguised. There's at least a chance -- unless data proves that it remains a fool's strategy, like throwing lots of hail marys (high risk but not beneficial) -- that a high percentage of routine onside kicking can give underdogs a real chance. Because when it works, it both gives the offense decent field position and steals a possession. When it doesn't, that's bad, but hey, we're talking underdog strategies.

In any event, it's an interesting discussion, and an eternal one: how do underdogs beat the big guys? How do the big guys keep from getting beat? Gladwell of course can't resist bringing up that greatest of underdog stories, the American Revolution, where a definite David strategy birthed a nation. And now we're the hegemony, the Goliath. I don't necessarily think any of this is relevant to our country's place in the world, but there's a reason why it all fascinates us so.

Triple Shoot Part 3 - Passing

Part 3 - Passing attack and screens

The drop-back passing game is initiated by our QB taking his drop to the inside hip of the play side Tackle (6 yards deep) while receivers are running route adjustments based on the coverage they are going against. We throw the ball out of a normal snap formation or a shotgun alignment. Throws are made to the receivers based either on “looks” or “reads”. A “look” is a progression from one receiver to the next, based on who should be open in sequential order. A “read” is the process of a QB reading the reaction of a specific defensive player (depending on the scheme that has been called), which in turn he will throw off of that defender’s movement.

Our drop back passes are all scheme-based as opposed to receiver’s running a passing tree. When a scheme is in synchronicity receivers will break on their adjustments as they are moving on the stem of their routes. Our receivers are trained to know what coverage they are facing by the time they are into the third step of their route. In the past, we would make a pre-snap determination of the type of coverage and execute routes accordingly. The benefit of our current system is that it is impossible to disguise coverage this late into the play. Regarding coverage recognition, this is taught by quickly assessing which family of coverage the defense is playing and then “feeling” our way to the appropriate breakpoint. This sounds much more difficult than it really is and we have developed specific drills that make this as easy as playing sandlot football.

Pass Schemes

There are six primary passing schemes which all “route adjust” based on the coverage we are facing. We can run many of these out of Even or Trips formations and we can even motion to Trips to change up the look we give defenses. The base schemes are called, Slide, Scat, Choice, Hook, Curl and Outside. Each scheme is named after the route run by the outside play side receiver. In every practice, we work on every scheme versus all coverage adjustments. “Tiger” Ellison once told me, “If you can’t practice the whole offense in a single session, you are doing too much.” Since the day he told me this in 1989 I have followed his advice to never add something without taking something away.

To write about all these schemes and adjustments would take a book or an instructional video. To give you a taste of the offense, let me share with you the top two schemes we most enjoy running, Slide & Choice! Slide has evolved from what “Tiger” Ellison called the Frontside Gangster and Choice comes from what was originally called the Backside Gangster.

Slide

The Slide scheme is the basis for all the passing game, in that we use this as a drill to teach 80% of our passing attack. The reason for this is that the route adjustments in Slide are executed at some point in the other schemes to a great degree as the QB rolls to the three-receiver side of the formation.

It all begins with the Slide route (In trips) versus a Nickel look (Cover 3 or Man-free). This route starts off with an outside release for 3 steps and from that point the receiver will read the coverage of the defender over him (Cornerback). If the defender bails out, the receiver will execute a Post on his 7th step. If he is playing a man look, the receiver will proceed to run a fade on this man to beat his man deep.

The #2 receiver will run a bubble route around the numbers on the field, making sure to look inside at the QB at a distance of 1 yard behind the line of scrimmage. The #3 receiver then executes a Pick route. The Pick route is designed to get over top of the outside linebacker that is covering the inside receiver. As he gets over the top of that linebacker, the receiver gets to a depth of 12-14 yards before he applies his “downfield zone rule”. The “downfield zone rule” is applied on the free safety in the following manner, “if the man in the zone is high over the top, the receiver will raise his outside arm and set it down to find the passing lane to the QB”. “If the man in the zone crosses the face of the receiver, the receiver will then run a thin post and expect to score.”

The QB will read the Slide route and throw it if it is open, if not, he can then check to the bubble and finally look to the Pick route, which has had the time to get open.

Choice

The Choice scheme is the way that we attack the single receiver side of the formation. The QB starts a roll toward the single receiver and the key to this route is that the stepping pattern of the QB must match up precisely with that of the receiver. The single receiver will release off the line of scrimmage and read the man over him (Cornerback) on the receiver’s 5th step. On that 5th step, if the man over him has bailed out he will run a “speed cut” Out on his 7th step. If the receiver has closed the cushion and the cornerback is outside leverage on the receiver, he will run a post and if he is inside leverage he will adjust his route to a fade.

On the backside of Choice, the three receivers will spread the backside of the field. We run a Go route by the #1 receiver (up the sideline) the #2 receiver will run a “backside stretch” inside the hash mark and the #3 receiver will run a control route at a depth of 5 yards to find a passing lane to the QB.

The QB will read the front side of Choice and throw it if his man is open, if not, he will look backside to the Stretch, then the Go and finally to the Control.

The Choice scheme is a great way to spread the field with our receivers and get the ball into the open seams on the backside, especially if the front side is cloudy.

[Ed. Note: For more on the "choice" concept, see here.]

Exotics

The Exotic plays are of two types, either a Screen to the Superback or a Convoy to one of our receivers. They are both set up with a pass protection simulation and we generally leak out three offensive linemen to block up field as the QB will influence the defense with his pass-action roll before throwing the ball to the back or the receiver.

Super Screen

This screen is a pass thrown to the back out of the backfield. Our line blocking is as follows: The front side tackle will influence the Defensive End for a 2-count before coming up field to block the first linebacker he sees inside. The play side guard will step to the direction of the screen and then release to block the support player while the Center will snap the ball and go down the line to block the first threat he sees, if there is no threat, he will turn around and block any defender that may be chasing down the screen.

The Superback must really sell this play by engaging the Defensive End momentarily before settling up in a passing lane behind the line of scrimmage. Our QB will either shovel the ball to him or pop it over the top of a defender depending on the rush of the defensive line.

Convoy

Our Convoy has been successful because the action of the QB is rolling away from the direction that he ultimately throws towards. The blocking scheme for Convoy works in the following manner: Our backside tackle will use a draw technique on the Defensive End and stay on him all the way in order to clear out a passing lane backside. The backside Guard will step to the direction of the QB roll and then release backside to block the support player. Our Center steps to the side of the QB’s roll and then releases backside to block the first linebacker he sees on the backside. The front side Guard will step to the QB roll before releasing backside to get the first man he sees, if there is no threat, he will turn in to block anyone that may be chasing down the receiver carrying the ball.

A convoy receiver will take two steps up field before coming behind the line of scrimmage and down the line into the passing lane for the QB. He will catch the ball and get up field to gain yardage through his linemen’s blocks.

Tomorrow, I conclude with a bit more on my background and the Triple Shoot's history of success.

- Manny Matsakis

Wednesday, 13 May 2009

Assorted links and notes - May 13, 2009

1. Bring back the old Spurrier: “I used to think I was pretty good coaching quarterbacks,” Spurrier said.

2. The Department of Sporting Jurisprudence: Do you have a right to be punished when you commit an intentional foul in basketball late in games?

3. Holy A-11 batman! The ACC now allows less than seven men on the A-11? Yes and no. As the good Doctor explains, they still can't have more than four players in the "backfield" (i.e. anyone not on the line) -- the idea is to prevent penalties when the offense has only ten men on the field.

4. Let me just go ahead and say no: I spent a substantial amount of time this offseason researching Michigan's offense (the results of which are to published, but not necessarily on the web -- though I hope to eventually get it out here or elsewhere that can be linked to). I will admit that I went into it thinking that there was some looming structural/strategic problem with Rodriguez's offense -- that's just my bent. Players win games obviously but I like blaming coaches more, and in any event all coaches have to work with what they have. But I quickly decided that, yes, there were things for Rodriguez to work on, but the biggest thing for Michigan was just to find a quarterback, any quarterback really. And, though he is but a wee true freshman, and a rather wispy one at that, Tate Forcier does appear positioned to at least be better for Michigan and Rodriguez than anyone they had last year.

Which is why I found recent transfer Steven Threet's comments so surprising:

Threet said he has no indication what will happen in fall camp but figures the tipping point will be decision-making, which gives Sheridan a chance to play.

"I feel like Tate has a good opportunity coming in early with the extra reps in the spring and that should be beneficial," he said. "But Nick does a good job of executing the offense the way they want it to be run. People may point out the physical things Tate or Denard may have at a physical advantage, but a lot of time at quarterback in this system comes down to decision-making."

"Nick" here refers to Nick Sheridan, who was statistically the only quarterback in the Big 10 worse than Steven Threet (unfortunately neither could run, and both of course played for the same team). Brian Cook convulses at this thought, as no doubt he still has night terrors about last season:

I can't seriously believe Sheridan executes the offense the way the coaches want it to be run . . .

. . . unless Threet means they've given that side of the ball a cigarette and a blindfold. Sheridan's decision-making last year was not a strong suit. . . . Why am I even spending time on this? The chances Sheridan takes a snap over a healthy Forcier are 0.001%. Seriously, people.

I agree. Yet, Forcier could always get hurt, and what had been relegated to nightmares of 2008 could, Freddy Krueger-style, reenter the real world. (H/t mgoblog and Dr Saturday).

5. How much does passing predictability (i.e. the more likely it is that an offense will throw) affect the offense's success rates? Lots of wonky stuff at Advanced NFL stats, but the punchline: "Going from about 50% predictability to 90% predictability costs at least 1.0 Adj YPA." Read the whole thing.

6. Mike Leach interviewed by Bitter Lawyer. Breakdown: Law school had far fewer "gorgeous girls running around" than undergrad; although in law school he discussed contracts, they were "kind of like a Leprechaun. I had heard of them, but I hadn’t actually seen one"; he wants a 64 team playoff to replace the BCS, with the remaining teams playing in some kind of NIT substitute; and he actually comes across as rather normal in the whole piece. (H/t doubletnation).

Triple Shoot Part 2 - Run game and play-action

Part 2 - Run Game and Play passes

The general makeup of the offense includes a run game, play passes, drop-back passing attack and exotics. The following is an overview of each area of the offense:

Run Game

This aspect of the offense is broken up into the Belly series, Trap series and Dive series. Our linemen work daily on their zone, veer, trap and double team blocks in order to maximize our consistency in rushing the ball.

The primary series of the offense is the Belly series, which is influenced by triple option (Hambone) and zone blocking. This was also complimented by a backfield action that I was able to glean from “Dutch” Meyers book, Spread Formation Football (albeit, he did this out of the shotgun) and some basic Wing-T concepts. The Belly series consists of the Pop Out (I have heard it also called the Jet or Fly Sweep) and the following dive plays, Veer and Zone as well as the change-up plays of the Option and Reverse. The key in executing each of these aspects of the Belly series is in the actual “ride” of the motion receiver by the QB and the subsequent fake or hand-off to the Superback, in order to draw attention to the potential Pop Out around the edge or the dive play to the back. Ideally, our Pop Out and dive plays will look the same for the first 3 steps and then become the actual play called prior to the snap of the ball. The change-up plays of Option and Reverse are designed to take advantage of fast flowing linebackers and defensive line slants.

Pop Out

Zone

Veer

Option

Reverse

Play Passes

The key to the play pass is that for the first three steps of the run series associated with it, the backfield and blocking must stay consistent (Bill Walsh). I know we are coming along when we stop the video at this point and we are not be able to tell if it is a run or a pass. Play Passes are called when the secondary is rolling or linebackers are so keyed-in to the run series that they disregard the potential of a pass over the top.

Our base play passes are executed off of our top run series, the Belly series. We practice two primary play passes, one to the front side (Wheel) and one to the backside (Switch). Regarding play pass protection, we put the Superback on the front side linebacker as we fake the Pop Out play and all the other linemen are aggressive in their execution of selling the run play.

Even Wheel

The Wheel is run out of our Even (balanced) formation and this play is good versus Nickel or Dime coverage. The play begins with the inside receiver coming in motion, the QB will then ride the receiver on a Pop Out fake as he turns to the oncoming receiver. The action will continue with a fake to the Superback. The QB will then set up just outside the play-side Guard and throw the Wheel combination. The QB will look to throw the ball to the Post first, then to the Wheel up the boundary. Often times the Wheel is thrown to the back shoulder of the receiver.

Receivers will take their first 3 steps (as if stalk blocking) and then break into their routes. The outside play-side receiver will break on a Post (5th Step) while the inside receiver will run through the breakpoint of the Post route.

Load Switch

The Switch route is run out of one of our trips formations (Rip or Load) and this play is also good versus Nickel or Dime coverage. The play begins with the number 3 receiver backside coming in motion for the Pop Out fake. The QB will simulate the same action as he did in Wheel. This time he will look backside to the Stretch route, which is running up inside the backside hash mark.

The two backside receivers will run the Switch combination on the backside in the following manner. The outside receiver backside will come first and get inside the hash mark at a point 7 yards up field while the number 2 receiver will run through the point where the outside receiver crossed his face and he will continue up the sideline. The outside receiver is responsible to read the deep zone defender over him. If that man is a Cover 3 safety, that defender may run downhill to tackle the Pop Out and if he does that, the receiver will continue on a thin post. If he stays high over the top, then the receiver will break his route flat at a depth of 12 yards to get open underneath the free safety. The Cover 2 conversion is predicated on the action of the backside safety. If he rolls to Cover 3, then the receiver will apply his Cover 3 rules. If he stays on the hash mark, the receiver will break it flat at 12 yards.

The QB will look to the backside Stretch route adjustment first and then to the route up the boundary. The boundary route is often times a back shoulder throw.

[Ed. Note. For more on the "switch" concept, see here.]

Play passes are often adjusted as we get through the season to take advantage of how defenses are geared up to slow down our Belly series.

Tomorrow, an overview of the dropback passing game.

- Manny Matsakis

Tuesday, 12 May 2009

John Madden knows more football than you

Content-wise . . . it's clear that Madden knows a whole heck of a lot about football[.] There's more really good football content that shows off Madden's expert status in any given 10 pages than in half the books I've reviewed on here. One Knee is now 23 years old, and in that time about all the rules changes Madden has suggested have come to pass, and generally because they were quite sagacious. Some random examples of football knowledge: talking about the importance of the strength of a defensive lineman's fingers-Bear great Dan Hampton, whose knees were famously ravaged, didn't seem to mind all that much, saying "I'd rather have a knee go than my fingers." As just a casual watcher, I know hand play is important for linemen, but it's not something I notice regularly or pay a great deal of attention to, but reading something like that makes me want to bust out the tapes and compare, say, Haynesworth's precise play in the playoff game against the Steelers his rookie year versus this year. Another thing -- Madden's first job as head coach was leading the Raiders. He knew he didn't have enough experience at game management to be successful. He could try game-planning, but it's tough to simulate the same type of rhythm and unpredictability within structure. So, he attended local high school games in the Oakland area and basically called plays as though his team was in that situation-on 3&8 from the 34, how do I attack this team's defense. Simple, but a very effective strategy. . . .

. . . Still, this is one of the best couple books I've reviewed on this site. I originally read this as a library book, but I'll be ordering both a copy of this one for my library and a copy of Madden's first book as well. Not recommended for getting a sense of the modern game, but enthusiastically recommended for fans looking for an enjoyable book written by an expert and who can stand the dated factor.

The "Triple Shoot" Part 1 - History and overview

Part 1 - Historical Perspective

It all started with a fascination of the 3 distinctly different offenses the Wing-T, Run & Shoot and the Georgia Southern Hambone. From there it evolved with specific influence and personal contact with the following coaches, Ben Griffith (Inventor of the Hambone), Glenn “Tiger” Ellison, Darrell “Mouse” Davis and Bill Walsh. As an additional note, Leo “Dutch” Meyer’s book, Spread Formation Football gave me an idea on how to create an explosive rushing attack (albeit, it was not the purpose of his book). Having started American Football QuarterlyÆ in 1993, while waiting to take a job at Kansas State University, gave me access to all of the aforementioned individuals, except coach Meyer.

It all started with a fascination of the 3 distinctly different offenses the Wing-T, Run & Shoot and the Georgia Southern Hambone. From there it evolved with specific influence and personal contact with the following coaches, Ben Griffith (Inventor of the Hambone), Glenn “Tiger” Ellison, Darrell “Mouse” Davis and Bill Walsh. As an additional note, Leo “Dutch” Meyer’s book, Spread Formation Football gave me an idea on how to create an explosive rushing attack (albeit, it was not the purpose of his book). Having started American Football QuarterlyÆ in 1993, while waiting to take a job at Kansas State University, gave me access to all of the aforementioned individuals, except coach Meyer.In the early 1990’s, I was working on my Ph.D. and while finishing my coursework I began a research project, which evolved into the Triple Shoot Offense. The title of the dissertation project was, “The History and Evolution of the Run & Shoot Offense in American Football.”

Development of the Offense

Researching the state of football and developing axioms and creating postulates based on those axioms created this offense. My initial axioms of the game were as follows:

- 1. The game of football has freedoms, purposes and barriers that give spread formation attacks a distinct advantage.

- 2. A systems approach to football has the greatest potential for success over a period of time.

- 3. When players are more knowledgeable about their system than the opponent is theirs they have the greatest potential for success.

- 4. A balanced approach to offensive strategy has the greatest potential for success over a period of time.

- 5. A system that appears complex, yet is simple to execute will stand the test of time.

These following postulates were the results of analyzing the previous axioms:

- 1. Spreading the field with offensive personnel creates mis-matches and distinct angles to attack the defense.

- 2. Utilizing a no-huddle attack enables an offense to control the clock and give the players a better understanding of the defense they are attacking.

- 3. A 2-point stance by offensive linemen gives them better recognition and a lower “center of gravity” at the point of attack.

- 4. A protection based on the principle of “firm: front-side & soft: backside” enables an offense to take advantage of any defensive front by keeping them off balance.

- 5. Run blocking schemes that combine Veer, Zone and Trap blocking enables an offense to run the ball versus any defensive front.

- 6. Pass schemes that adjust routes based on coverage on the run will open up holes in the secondary.

- 7. Quarterback decisions based on looks & reads give the offense the ability to release the ball anywhere from 1 to 5 steps. This will minimize the amount of time necessary for pass protection.

Triple Shoot Offense Defined

The Triple Shoot Offense is a systems oriented, no-huddle, four receiver, one back attack that is balanced in its ability to run or pass the ball at any time during a game. It is predicated on spreading the field and attacking a pre-ordered defense with blocking and route adjustments after the play begins.

Ordering Up The Defense

The concept of “ordering up the defense” is one that I learned from “Tiger” Ellison. His concept was to place a label on each defensive man (numbering), and from that to designate a specific defender that would tell his players what to do, either by the place he lined up before the ball was snapped or by his movement after the snap.

The Triple Shoot Offense took that information and decided to look at defensive alignments based on the way they matched up to a 4 receiver, one-back formation and designated defenses as either Nickel, Dime, Blitz or they were considered unsound. Nickel looks are based on six men in the box with one free safety, Dime looks have five men in the box with two safeties and Blitz is recognized when there are seven defenders in the box and no safety over the top. Anything else is an unsound defense that we hope a team is willing to attempt.

In order to keep defenses in these alignments we utilize a variety of concepts, from widening our inside receivers to calling specific plays that put a bind on any defender that tries to play both the front and the coverage. When we get to the point where we can do this, the offense is at its most optimum in production.

Tomorrow, the run game and play-passes.

- Manny Matsakis

Monday, 11 May 2009

More on Gladwell and underdogs

This is very important for a coach like Kentucky’s Rick Pitino. His game plan of three pointers and pressing defense is a high variance strategy, one that an underdog should take, not a favorite. This high variance strategy is how he got his unknown Providence team to the final 4 in 1986. This is how his Kentucky team came back from a record 33 point deficit a year ago. But continuously applying this high variance strategy on a team with great talent like Kentucky is asking for an upset. Kentucky has been among the favorites to win the NCAA title two out of the past three years, only to fall earlier than expected. Again this year, they were favorites, being preseason #1. But their high variance game plan cost them last night against Massachusetts. And it will likely cost them later on this season. Despite Kentucky’s immense talent, coach Rick Pitino’s risky game plan makes the team more susceptible to upsets.

Sunday, 10 May 2009

Assorted links and notes

1. Great article on one-back (six man) pass protection.

2. BCS mania: The good Senator has consistently been one of the best voices on this BCS debate, so read up here and here. (And Dr Saturday has an informative response.) I generally agree that the whole thing is much ado about nothing, and a secret part of me wants the "PLAYOFFSSSS!" contingent to win so that they realize the imperfection of what they merely assumed would fix all the sports' ills. Specifically, absent from the debate -- along with an elementary understanding of the economics of college football, or just economics at all (with claims of socialism being thrown around) -- is an understanding of what National Champion is supposed to mean. The BCS does a pretty good job of finding the best overall team in terms of who would probably be favored to win against any other opponent. That excludes teams like Utah, but is a playoff unequivocally the best option? Were the New York Giants better than the New England Patriots two years ago? No, of course not. Maybe there are other benefits, but I don't think "fairness" is one of them. Or, as the Senator notes, if you want to talk about "fairness" in a meaningful way, then you're in the territory of "revenue sharing," which the NFL has to keep parity but is a strange thought when it comes to college sports.

3. Most important stats? Trojan Football Analysis ran some basic regressions on offensive and defensive stats to see which have the highest correlation with winning. Unsurprisingly -- for readers of this blog at least -- passing yards per attempt came out with an R-squared (a measure of correlation, basically) of 0.40, the second highest offensive stat, behind only scoring offense itself. Passing yards per attempt came out higher than yards, rushing per attempt, turnovers, red zone, and others. (But also see this post from the Sabermetric Research blog on the limits of R-squared.)

4. It's good to see that Kansas State fans can have a good laugh at their own expense. (H/t Sporting Blog).

5. The Mike Leach contrarian: T. Kyle King of Dawg Sports opens up two barrels of eloquent assault on Mike Leach. King says he doesn't know anything about the guy personally, but finds Leach's public persona -- particularly his recent comments about NFL coaches and the past two Texas A&M staffs -- "rude," "childish," and "churlish." (Nice.) I can't do the whole post justice (go read it) but a lot of it is based on the question: What in Leach's resume gives him the right to "demean[] his coaching coevals?" I've already said my bit, though I agree with Kyle that one reason Leach gets so much love from coaches (well, at least ones who aren't the subject of his criticism) and commentators is that he good for such quotes. The only thing I'll add is this: most of Leach's comments have come in the context of him trying to defend his players, though in his case it is special because much of the criticism of the players reflects on him. Most perspicuously, think Graham Harrell not getting drafted -- a "spread" quarterback. Harrell, unlike past Leach quarterbacks like Sonny Cumbie or Cody Hodges, turned down several other fairly big name schools to play for the Dread Pirate, and much of the criticism of Harrell came in the form of questioning what Harrell had been doing under Leach's tutelage. By contrast, guys like Stephen McGee -- who I actually assume that Leach had always respected as a player but probably marveled at how lamely he was used -- were drafted in spite of all coaching.

In other words, I think Leach took the Harrell situation personally in that, to him, the only apparent difference in the minds of NFL scouts between Harrell and McGee was that Harrell had the unfortunate distinction of being coached by Mike Leach to throw for a jillion yards while McGee got no coaching whatsoever, other than how to run some mediocre option. This might not be accurate, but it explains Leach's defensiveness. I also firmly believe that Leach is honest when he said his comments about McGee and A&M was directed at the coaches, not the player. To criticize other coaches for misusing a talented player is fairly brutal, especially considering Leach's consistent success against A&M. Now, I also sympathize with Mike Sherman's confusion about how to deal with barbs from a guy like Leach, but that's the world he's in. (The Mangini Crabtree situation was similar: he rushed to the defense of a player. And again, maybe not in the best of judgment, but not the best judgment for Mike Leach is different than it is for most.)

6. Four-verticals: Cheesehead TV identifies an example of the Green Bay Packers running the four-verticals concept from a five-wide set. (For another example of four-verts, check out this post.) See the clip on the NFL website here.

7. Try this at home: Speaking of video, I loved this old video of Bobby Bowden explaining the "Puntrooskie." People forget that Bowden, with the help of some good Florida talent, completely resuscitated that program and was himself a mastermind of the one-back three-wide pass attack Florida State rode to preeminence. In his way, Bowden was one of the first to go "spread," though it was a Sid Gillman, pro-style attack. (H/t EDSBS.)

8. Malzahnitude: The Joe Cribbs Car Wash combines two things I generally enjoy but am not universally enamored with: Gus Malzahn (new OC at Auburn) and Malcolm Gladwell. It's worth the read. One brief thought on Malzahn, however. Gus's big thing is that he believes in tempo. Of course, he hasn't really had a chance to go breakneck speed yet at Auburn (at least by the reports of those who have seen both Tulsa, his former stop, and Auburn practice), though the offense is apparently looking much better already. Ironically, he's improved -- over both Tuberville's prior offense and the Tuberville Franklin mash-up -- by just bringing some sound, simple schemes. Sure he has a lot of window dressing, but that offense had just gotten bad. Yet, at least in year one I'll be surprised if he works miracles.

What they did at Tulsa was wonderful, but Herb Hand -- who brought the zone blocking aspect of the running game to go with Malzahn's pace and power game schemes -- was an integral part of the Tulsa attack: they were co-offensive coordinators for a reason. And though Malzahn seems reasonably committed to the running the ball, he was always a pass first guy, so we'll just have to see how that flies without a true quarterback. And the X factor is Chizik, the head coach. Even if Malzahn's offense is good, there are few defensive minded guys who appreciate a three-and-out (which can happen to any offense) that takes about eight seconds to occur. How long is his leash? Time will tell.

What I've been reading

2. FDR: The First Hundred Days

3. Notes from Underground

4. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness

About the book: I liked it, but I'm not raving. It takes a couple of behavioral economics' biggest or best ideas and stretches it out over the course of the book. I think it would make a great article (indeed, it has made several) but the book is uneven. The early chapters read like a high school level or at best freshman undergraduate level explanation of ideas like anchoring, availability, and representativeness -- all important heuristics to understand, but stretched out too long. But then, the book switches course to specific applications, and its choices are the minutiae of some rather byzantine laws and regulations, from Medicare Reform to potential social security reform. These are not gripping chapters.

I leave aside the broader political questions hovering over the book in terms of judging it (and the book tries mightily to stay apolitical). I note that Thaler and Sunstein call their approach "libertarian-paternalism" -- the idea is that we want to maintain maximum choice but nevertheless design the architecture in a way that makes it easier for people to make the right choices, or even if they make no choice at all. The only vaguely political comment I do have is that Thaler and Sunstein spend a lot of time justifying the "paternalistic" aspect to would be libertarians who are skeptical of all government interference. And indeed, there is much criticism of the book from this faction. But, since the book's initial conception, the political winds have shifted somewhat, and I would have enjoyed a more thorough defense of the "libertarian" half of their approach. The authors are committed to free choice, yet they mostly assume that everyone is with them on the point. This is not to say they are not, but debate is always good -- where there's light there's usually also heat.

5. On Writing Well, 30th Anniversary Edition: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction

* This deserves its own post, but economist Kevin Hassett has developed NFL draft rankings based on the Massey-Thaler paper. Who did the best in the 2009 NFL draft? I'll let Hassett and Thaler. Via the Nudge blog:

Hassett identifies four winners: New England Patriots, Denver Broncos, Detroit Lions Lions, and New York Giants.New England’s coach, Bill Belichick,…ditched his first-round pick altogether and loaded up on four second-rounders. In addition, he traded some of his later picks for other teams’ second-round picks next year. The big news is that the Giants maneuvered to get two second-round and two third-round picks, elevating their final scores.

The big losers were the Washington Redskins, the New York Jets, and the San Francisco 49ers.The Redskins once again revealed their extreme economic ignorance, trading away their second-round and fourth-round picks…The Jets made a classic error, falling in love with University of Southern California quarterback Mark Sanchez and virtually guaranteeing they will have a large number of undrafted scrubs on their roster. Given the high salaries at the top of the draft, Sanchez will probably not generate much value above that demanded by his salary, even if he becomes a superstar.

Thaler loves the Patriots draft and also gives a positive review to the Cleveland Browns. After entering the draft with the 5th pick overall, the Browns traded down three times to take center Alex Mack with the 21st pick, plus defensive end Kenyon Coleman, quarterback Brett Ratliff, safety Abram Elam, a second round pick from the Jets, and sixth round picks from the Buccaneers and the Eagles. That’s a lot of chances to pick up some solid starting players. Football pundits didn’t think so highly of the Browns draft, but none of them are economists.